One of the honey bee’s worst enemies is a tiny mite called Varroa destructor.

It is small and yet highly dangerous: the Varroa destructor mite is the most destructive enemy of the Western honey bee (Apis mellifera). The parasite has now spread to almost all parts of the world – except for Australia – and is a serious threat to bee health. Without human intervention, a bee colony infested with mites will typically die off in these regions within three years. In addition to the threat posed by the Varroa mite itself, there is also the danger of secondary infection from various mite-vectored diseases, which have also become more widespread and additionally weaken the bee colonies. The parasitic Varroa mites – much like ticks – transmit diseases that often prove fatal to adult honey bees and their brood. Combating the mite is a difficult task for researchers. This is because – despite a number of promising ideas – they have not yet managed to develop simple and long-lasting treatments for fighting the bee parasite, nor have they yet managed to breed a Varroa-resistant strain of the Western honey bee.

The Expansion of the Varroa Mite

The Varroa mite is originally native to Asia, where it was first discovered on the island of Java in Indonesia over 100 years ago. The mite initially preyed on the Asian honey bee (Apis cerana). But over thousands of years the bee successfully adapted its behavior to the parasite. The bees fend off the mites through their intensive cleaning habits in the hive, thus minimizing harm to the colony. When European settlers brought the Western honey bee (Apis mellifera) to Asia, it also fell prey to the Varroa mite. Through these infested colonies the parasite was then introduced to Europe, where since the 1970s it has continued to spread. Recent genetic investigations have revealed that Varroa jacobsoni comprises 18 different genetic variants with two main groups: Varroa jacobsoni and Varroa destructor. Varroa destructor, the newly identified type, inflicts a great deal of harm in Europe, North America and elsewhere because the Western honey bee lacks sufficient defense mechanisms. Clearly, the equilibrium between Varroa destructor and the Western honey bee has not yet been established. The mite is now found in many areas of the world: it is common not only in China and Russia but also in Central Europe and North and South America. Even New Zealand and Hawaii reported cases of infestation in the first decade of the 21st century. Australia is the only part of the world where the mite has not yet spread, mainly as a result of intensive biosafety protocols at the borders.

The Biology of the Parasite

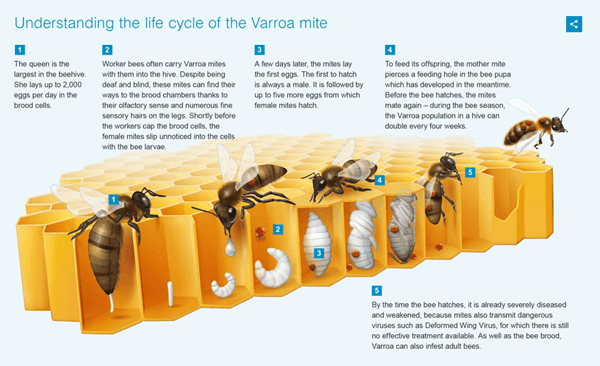

Varroa destructor literally means “destructive mite.” And although the parasite’s name more or less says it all, this tiny arachnid is not much larger than a millimeter and lacks hearing and sight. The body of the mite has four pairs of legs and piercing and sucking mouthparts. It uses the numerous sensory hairs all over its body as receptors to sense its environment. The Varroa mite’s flattened shape and the suckers on its feet enable it to optimally grip the bee’s body. It uses its mouthparts to pierce the bee’s exoskeleton and feed on its hemolymph, a circulatory fluid similar to blood.

The Reproduction Process of the Varroa

The parasite preys on both adult honey bees and their brood. Varroa females can also survive outside the brood cells by attaching themselves to adult bees. However, the parasite only reproduces in the sealed brood cells of the honey bee. Shortly before the brood cells are capped, the Varroa female mites enter and crawl to the bottom of these cells – they protect themselves from the bees that tend to the brood by hiding under the larvae. Here they first immerse themselves in the liquid brood food. Once this is depleted, the Varroa mite feeds directly on the bee larvae. The parasite has strongly adapted to its host in terms of habitat and food.

THE VARROA POPULATION CAN DOUBLE EVERY FOUR WEEKS DURING THE BREEDING SEASON. IT CAN GROW FROM 50 MITES UP TO AROUND 3,200 MITES FROM THE BEGINNING OF FEBRUARY TO THE END OF AUGUST – WHICH ENABLES IT TO WIPE OUT EVEN A STRONG BEE COLONY OVER THE WINTER.

Transmission of Honey Bee Viruses

Unlike its South-East Asian counterpart, the Western honey bee lacks sufficient defense mechanisms to fend off the non-native parasites. Infested honey bees are weakened as a result of the mites feeding on their hemolymph, which puts a strain on the bees’ immune system. This adversely affects their performance and shortens their life span. When the parasite feeds on the larva, it also transmits dangerous viruses directly into the bees’ hemolymph. The viruses can spread and harm the bees during their vulnerable development stage. Varroa increases the extent of the infection, because in the hemolymph, many viruses become deadly. Since there are no effective medicines to treat honey bee viruses, control of the Varroa mite to reduce the spread of viruses is essential. One such virus that is very widespread is the deformed wing virus (DWV), which can occur both in the brood and in adult bees. Often an infection does not produce any visible symptoms, but if the parasite transmits the virus to bee pupae, the young bees will develop deformed wings. These bees are unable to fly – and have a shortened life span compared to healthy bees. The Varroa mite also transmits other viruses such as the acute bee paralysis virus (ABPV), which can infect adult bees and larvae alike. It is primarily found in fat body cells and in the bees’ salivary glands, but does not produce any typical signs of disease. The mite transmits ABPV directly into the bees’ hemolymph. From there it spreads to the vital organs: once in the brain, the virus induces behavioral disturbances and impairs orientation and development – all of which can have lethal effects on the bees. An infection with ABPV is particularly critical in the case of winter bees – it severely affects their ability to survive until spring.

THE VARROA MITE HARMS HONEY BEES IN VARIOUS WAYS:

– IT WEAKENS THE BEE’S IMMUNE SYSTEM, CAUSING DISEASE PROGRESSION TO BE MORE ACUTE.

– IT TRANSMITS VIRUSES THAT SPREAD QUICKLY WITHIN AND BETWEEN BEE COLONIES.

– IT TRANSMITS VIRUSES DIRECTION INTO THE BEES’ HEMOLYMPH – PREVIOUSLY HARMLESS VIRUSES CAN THUS BECOME LETHAL.

Infection with the Varroa mite

The varroa mite spreads from hive to hive through contact with bees from other colonies, even to colonies located several miles away. During natural and assisted reproduction and robbing, the varroa mite travels on the back of the host bee to nearby hives, where it continues to multiply and spread.

Combatting the Varroa mite

When it comes to improving honey bee health, one of the main activities of beekeepers in Europe and North America is fending off the Varroa mite. In fact, the beekeepers’ most important task – particularly in late summer – is to minimize the level of colony infestation. This is crucial to ensure that sufficient numbers of bees survive the cold months of the year, thus enabling a strong colony to develop again in the spring.

Homelabvet has some tips on this.

There are some quality and effective medicines that you can use against Varroa mites:

Amitraz Plus strips (active ingredient – Amitraz and Thymol), AntiVaro strips (active ingredient – flumethrinum), Taktic Amitraz amp (active ingredient – Amitraz), Taktic Amitraz 25ml (active ingredient – Amitraz), Taktic Amitraz 50ml, Oxalic Acid, Flumetriy (active ingredient – flumethrinum), Amipol – T (active ingredient – Amitraz and Thymol) – this is an analog of Amitraz Plus strips.